THE PLIGHT OF THE MODERN CHINESE RESTAURANT: UNDERSTANDING THE EFFECTS OF CORONAVIRUS ON CHINESE RESTAURANTS THROUGH A DEEP EXPLORATION OF THE HISTORY OF CHINESE FOOD IN AMERICA AND XENOPHOBIA

Abstract

In this piece, we attempt to use the history of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. to better foreshadow the differences in COVID-19’s lasting effects on urban Chinatowns that serve authentic Chinese food and Chinese restaurants in more suburban, primarily non-Chinese neighborhoods that primarily serve takeout Chinese food. We also evaluate how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates existing populist sentiments and draws on implicit biases regarding Chinese Americans, putting both types of Chinese American cuisine at risk.

The following paper addresses these two different types of Chinese cuisine in relation to the different neighborhoods because of a discussion we had about our relationships to Asian restaurants in our respective neighborhoods. Two of our authors live near two large Chinatowns (New York and Boston) and another lives in the suburban town of Cornwall. Regardless, these Chinese locations are extremely important to us.

Chinatown is often overlooked as a place of unique culinary expertise, a hub of language exchange, and a cultural safeplace for Chinese Americans. Such a loss would cause a huge hole in part of the American immigration narrative, as well as a loss for new generations who would no longer have a cultural epicenter. Chinese restaurants outside of Chinatown are equally important, assimilating Chinese cooking techniques and ingredients into the American palate.

Given its historical resilience and internally facing nature, it's likely that Chinatowns will persist through the pandemic. The virus and consequential xenophobia, for independently-owned Chinese restaurants outside of Chinese neighborhoods however, will be far more destructive.

Introduction

The dissonant clamor of voices mixed with hearty laughter soothes the soul. Two pairs of wooden chopsticks have a bashful encounter in a dish of bok choy, and one nudges the other to go first. “多吃点儿, 多吃点儿!” Eat more, eat more, Aunty beams, using her chopsticks to heap yet another serving of braised pork onto one slightly horrified child’s plate. The glass Susan lazily spins around the table, intercepted by clammy fingers, serving spoons, and yet more chopsticks playing a game of Hungry Hungry Hippos. Half a bowl of white rice is plopped onto a plate, then passed to the right.

From hot pot to street snacks— 小吃, little eats — to just a regular old dinner out, communal style eating is the heart of authentic Chinese eating culture. Eating together is a way to express love and share joy. Leave the cozy indoors of restaurants to find vibrant signs, yelling fruit stand owners, and pungent smells of fish from one street to soy milk on the other: Chinatown’s personality is irreplaceable.

A scene like this would have been considered ordinary in Chinatown mere months ago, but now feels utterly unimaginable.

Aunty’s extended family has a restaurant in Bakerville, the epitome of a peaceful suburban town. But with COVID-19’s emergence, they feel particularly perturbed. Announcements of hate crimes decorate the headlines of all media outlets and while Aunty often suggests they sign up to be a grubhub vendor, they wonder if the risk is worth it.

In today’s COVID-19 climate, everyone must ask: Will Chinatowns, immigrant enclaves concentrated with small businesses and reliant on a steady stream of customers, survive the xenophobia it is encountering? What about takeout restaurants outside of Chinatown? Or will stir frys, communal style dinners, Chinese vegetables— even the heavily Americanized kung pao chicken and egg rolls— disappear off the menu forever?

Even with the recent climate of xenophobic populism and uptick of anti-Asian hate crimes, we believe Chinatowns’ internally directed natures and historical resilience will allow it to persist even after states reopen, but that take out restaurants outside of this Chinese bubble are the ones who are truly at risk. An exploration into the history of Chinatowns and early Chinese food in the U.S. shows these neighborhoods' resilience to white disdain, deliberate attempts to destroy Chinatown for real estate, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and even being scapegoated for the black plague. One hundred twenty years after the bubonic plague, COVID-19 will now test the resilience of Chinese restaurants with an almost exclusively non-Chinese consumer base.

Section I: Chinatowns and Xenophobia During the Coronavirus Pandemic

Chinatowns Today

Empty seats, flickering OPEN signs, and eerie silence suffocate a city usually bustling with eager tourists and customers: Chinatown. Following the first wave of news in December about the outbreak of a virus in Wuhan, China, Chinatown restaurants and businesses across the globe began to immediately falter in sales. Tourists stopped visiting hotels and eating at beloved Chinatown restaurants. Even locals began to avoid Chinese restaurants, shops, and other businesses out of the association of Chinatowns and Chinese-Americans with COVID-19 by the general public. Foot-traffic plunged just ahead of the Chinese Lunar New Year and Spring Festival tourist season as well, which is normally one of Chinatown’s most successful and profitable times of the year. In the past months, Chinatown, in the eyes of millions, has become eviscerated as the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, resulting in a staggering loss in business that has plunged thousands of business-owners and employees into a financial crisis.

Besides hurting individuals, the xenophobia brought about by the coronavirus threatens to permanently destroy communities, and Chinatowns seem to have the most to lose. Well before restaurants were forced to close, Chinese restaurants in Flushing, Queens had already begun reporting a 50% drop in sales. One hundred and twenty years after the bubonic plague hit Hawaii, people cannot shake the association of disease with the faces of Asian Americans. With the restaurant industry driven to unprecedented lows, it is uncertain if the Chinatowns will survive this round.

Currently, the Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York are facing more than a 70-80% decline in business. In an interview with NPR, Kevin Chan, the owner of the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory, reveals that this recent Chinese Lunar New Year was the “worst new year I ever had in my life,” and that he had been forced to lay off staff and turn off his machines in order to barely stay afloat— despite its status as a legendary tourist attraction and there being no positive cases of coronavirus at the time in San Francisco. Even when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited the San Francisco House district to reassure residents that any fear about the spread of coronavirus was unwarranted at the time, locals remained risk-averse to visiting Chinatown, depicted by the uniquely drastic loss in sales concentrated in businesses run by those by Asian Americans in comparison to other businesses. Despite having made great strides towards racial equality in the United States in the past few decades, the political climate of the United States and the Western world finds the story of struggling Chinatowns ultimately unsurprising.

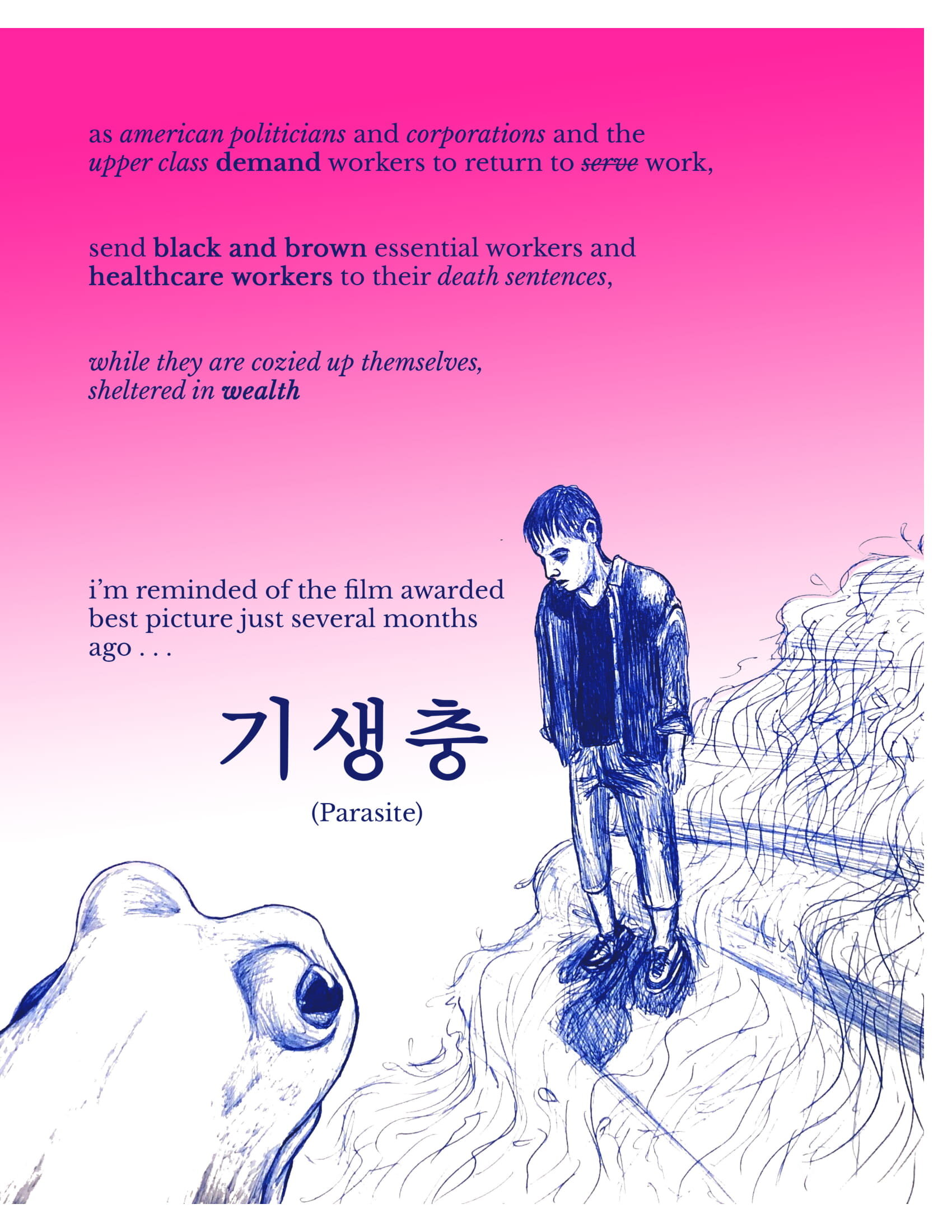

A Populist Climate

In the forty years that followed World War II, the developed world experienced an unprecedented period of growth, peace and stability, inciting a movement towards Postmaterialist views. Postmaterialists tend to emphasize “peace, environmental protection, human rights, democratization, and gender equality.” As the Silent Revolution argues, the postwar generation came of age in an environment where they did not have to worry about survival, consequently resulting in values that are more tolerant of new ideas and people. In the mid-to-late eighties, however, the developed world began to see a divergence of classes. Despite steady GDP growth, income inequality began to rise, eroding the middle class and tearing at the security in the West—a trend that has continued through today. In response, populist movements have gained enormous traction in Western countries, with the election of Donald Trump in 2016 often cited as one of the most prominent examples.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the greatest, if not the greatest, threat to existential security in modern history. Thanks to an increasingly globalized world, a virus that originated in Wuhan, China—a place most people had probably never heard of before a couple of months ago—has made its way to every corner of the world.

Since the stay-at-home orders began in mid-March, over 30.3 million Americans have filed first-time claims for unemployment. The official unemployment rate reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics at the end of April stands at a staggering 14.7 percent. As we enter into another global depression, this time coupled with a highly contagious and deadly disease, we must beware the danger of scapegoating. In times of “insecurity,” people tend to seek “in-group solidarity and a rejection of outsiders.” For populations with little exposure to Asian culture, like those in suburbia, the perceived existential threat is likely to be even greater than the real existential threat. Populism seems like the inevitable consequence of human nature’s tendency towards tribalism, and its potential fallout on Asian Americans will remain long after we are able to leave our homes.

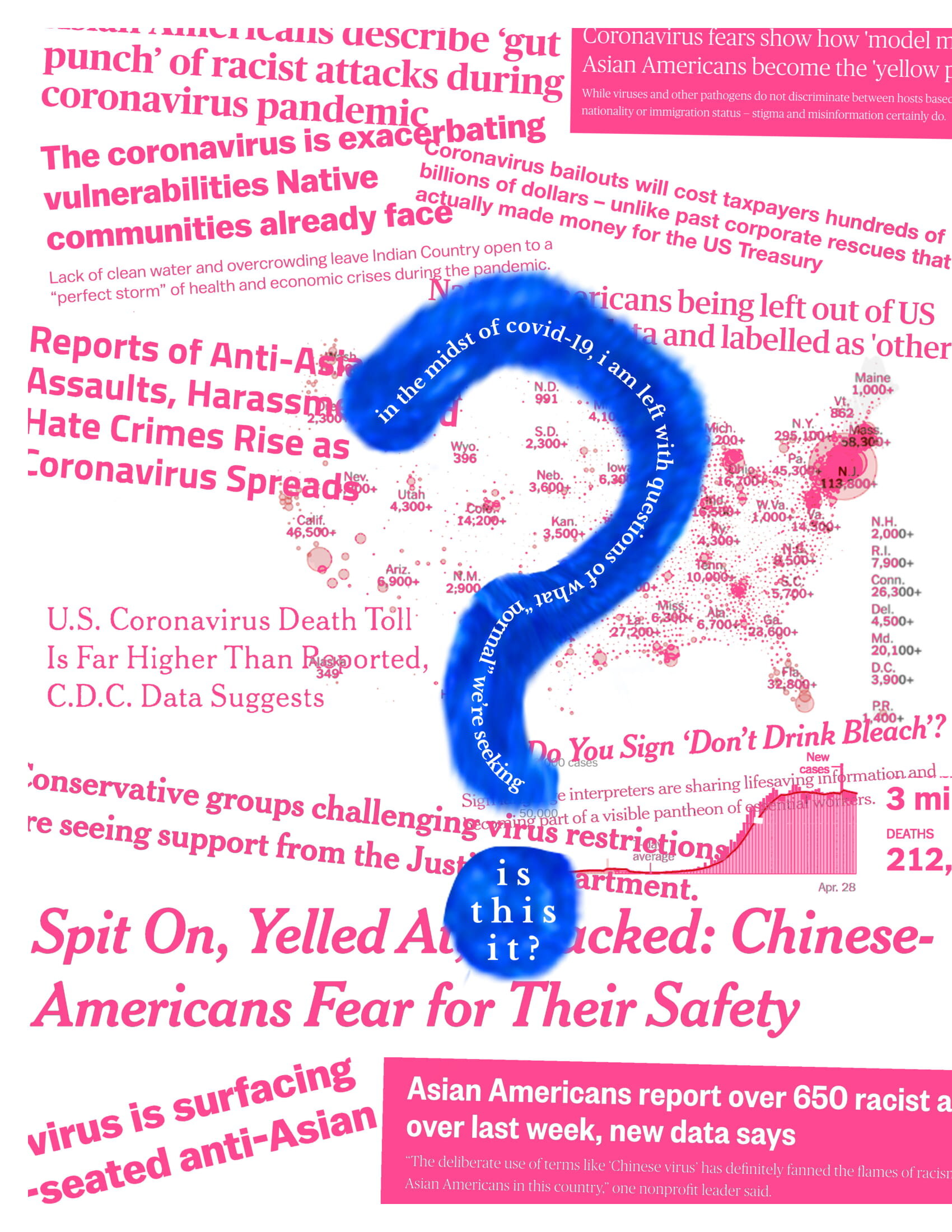

Consequences for Asian Americans

Poised against the backdrop of a rise in populism, the xenophobic consequences of the coronavirus have unsurprisingly already begun manifesting themselves. President Donald Trump referred to the coronavirus as “the Chinese virus,” in several Tweets back in March, eventually deciding to stop using the term after facing severe backlash from critics who feared the term would incite racism towards Chinese Americans. In addition to being dubbed the “Kung Flu,”these alternative names have been widely circulated across media outlets and used by conservative politicians. Indeed, xenophobic attacks against Asian Americans have become increasingly common, with instances of Asian Americans being avoided in public spaces and called racial slurs published in articles as early as the beginning of February, when the virus had not yet significantly impacted United States.

Since then, the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council has been spearheading a movement called “Stop AAPI Hate,” with hopes to document xenophobia targeting Asian Americans. Between March 19th and April 26th alone, the A3PC received 1,497 reports of racism against Asian Americans.

Today, the detrimental effects of deeply-rooted xenophobia mixed with the general fear and economic instability that has mounted due to COVID-19 on Chinese-American businesses are taking place in Sunset Park, New York, which houses New York City’s largest Chinese population. When interviewing some of the 74,000 Chinese immigrants, it is clear that the anti-Asian sentiment that has broken out over the rise of coronavirus has taken an enormous toll on the immigrants and workers that populate the community. An employee of Pacificana, one of the only dim sum restaurants in Sunset Park that still currently remains open, noted that they lost “about 90 percent, or maybe more, of our customers.” Most other dim sum restaurants in the area have closed, unable to stay afloat. Assembly member Yuh-Line Niou condemned the xenophobia and racism that has targeted the Chinese-American businesses in New York’s Chinatown, arguing that even though “every single one of our restaurants, our businesses, have the same safety inspections, commercial standards, and health codes as anyone,” people still are “urging others to avoid Asian American restaurants or businesses.” With the rise of COVID-19, the general American public and media has portrayed COVID-19 as something to be directly associated with Chinese-Americans and Chinatown – a harmful rhetoric that has always reared its ugly head amid global pandemics.

Furthermore, anti-Asian rhetoric has infiltrated all aspects of life for Chinese-Americans and workers, from verbal harassment on the street to physical assault to actions taken upon by the federal government. Residents of Sunset Park admitted that “a part of me is worried that the [federal government] is going to impact people seeking help if they are showing symptoms of something more serious,” after a series of raids by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents (ICE) prompted residents to stay indoors out of fear. Also, while wearing face masks has been recommended to protect individuals and reduce the spreading of the COVID-19 virus, for Sunset Park residents, “many community members have started to associate wearing face masks with xenophobia, so they avoid doing so because they don’t want to be attacked or discriminated against.” The anti-Asian racism that has skyrocketed due to the outbreak of COVID-19 has not only destroyed Chinese-American run businesses and restaurants across the country, but has injected fear for the safety of the Asian American community across the globe.

While Chinese food has become widely popularized in today’s society, the general public’s devastating aversion to Chinese food and restaurants today in response to the outbreak of COVID-19 demonstrates how prevalent anti-Asian xenophobia still remains deeply embedded in the social, cultural, and political fabric of society. This simultaneous celebration for the economic success of ethnically exotic Chinatowns while being vilified as filthy and diseased perpetuates the notion that we, as Asian Americans, are still foreign and racialized bodies out of place in Westernized cultures. Now, more than ever, must we open our eyes and hearts to the struggling Chinese-American populations that continue to face this degradation in the face of COVID-19.

These consequences are rooted in a long history of xenophobia against Chinese Americans and the reluctant assimilation of Chinese style foods into mainstream American culture.

Section II: Historical Contextualization of Xenophobia against Chinese Americans and Chinese Food

The Introduction of Chinese Americans and the Chinese Exclusion Act

Chinese food in America began as an important slice of home to early Chinese laborers. Chinese 49ers (1849) were the first overwhelming wave of Chinese immigrants to America. Initially arriving in response to the California gold rush, these immigrants did not find wealth in gold, but instead found opportunities for themselves by proving their work ethic and developing a community amongst themselves. Chinese restaurants were extremely crucial to this community, becoming the main place for resting, socializing, and networking as Chinese laborers could find food that resembled meals from home, and get it for as low as ten cents in 1878 compared to the twenty five cent dozen of eggs and engage with others of their native language and facing similar American trials, all in one place. Here, men discussed potential job opportunities and shared crucial resources. Railroad labor opportunities were one such opening for the Chinese immigrant community as these companies began to recognize the value of Chinese laborers who were cheap and reliable, and in 1870, when they were looking to build a railroad in Calvert Texas, hired these Chinese men in massive numbers. During this process, Chinese community leaders were successful in negotiating for Chinese ingredients such as ginger and cooking utensils such as the “frying pan shovels” and “forty sets of chopsticks.” This conveys the value of Chinese food to the Chinese community as necessities for their food, not higher wages, were their specified employment conditions. It also demonstrates their ability to advocate for themselves to maintain their communities despite work requiring them to stray further from their initial cultural centers. By ensuring the travel of Chinese food with them, they ensured Chinatown would always be nearby; restaurants always attracted other Chinese businesses, and these small Chinese enclaves began to be established all along the railroad.

For a brief period, Americans' attitude towards San Francisco’s Chinatown also began to shift as Americans began to view Chinatown as an exotic tourist destination. For the first time, Chinese food was not just being served exclusively to Chinese clientele. This success, however, was extremely short lived.

Towards the very end of the 1800s, Chinese people became the scapegoat for declining wages and fewer job opportunities, culminating in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. White miners, bitter with failure in California gold mines, flooded the cities for other low skill jobs. This influx of laborers in combination with the “discovery of gold in Australia,” which “brought on a financial panic...Prices, rents and values fell rapidly and many business houses failed,” caused wages to be glutted and left many unemployed. Americans shifted the blame onto the most conspicuous immigrant group at the time, the Chinese, because they acknowledged this group as a threat. “Californians found the work ethic of Chinese laborers (admirable),” and recognized their willingness to work hard despite low wages. Anti-Chinese sentiment grew out of fear of the potential of this capable group and eventually, this sentiment became law. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first in history to ban immigration and citizenship of an entire ethnicity. To give context of how ignorant and racist this document was, we have highlighted the passage “Mongolians are alien to our civilization, aliens in blood, aliens in faith...they are a degraded peoples,” from the writing of the Chinese Exclusion Act itself. Here, “Mongolian” is used as an umbrella term the document writers used for all Asians, to capitalize on images of the savage Genghis Khan.

History of Chinatowns: Disease and Resilience

Similar efforts were taken to scapegoat the Chinese for the bubonic plague, attacking Chinatown as dirty, nonnative (smelly), and connecting Chinese food to rats. In the 1900s, California was hit by the bubonic plague, a devastating epidemic spread from Asian trade routes to European countries and then the Americas. Not only was it deadly, assaulting the lymphatic system and causing “black boils that oozed blood and pus,” but it was also highly infectious. After the US public health service announced that this Black Death was spread through rats and fleas, people immediately found reason to blame the Chinaman. As previously mentioned, anti Chinese sentiment had already been established. In addition, San Francisco’s Chinatown was dilapidated to say the least. Property law at the time did not allow Asians to own land so they had to rely on well-networked white men who directed them to owners of tenement houses who preferred Chinese residents because they reliably paid their rent but themselves neglected their properties. The Chinese endured such conditions, deciding not to pay for any fixtures in order to send income back home. Chinatown’s unsanitary state was thus not a product of any uncleanliness of the Chinese but of neglect by property owners.

On top of that, other white businessmen who wanted to run Chinatown out of business finally saw an opportunity to claim Chinatown’s valuable real estate. They pushed for wholesale demolition of the area to create yet another sector of white commercial business, capitalizing on the dilapidation and filth associated with Chinatown. They claimed that the Chinese themselves bred disease with a particular emphasis on rats. This effort was so successful that a 1907 investigative report of the bubonic plague called it a “typical oriental plague,” a spooky parallel to Trump’s insensitive naming of COVID-19 as the “Chinese flu.” These associations resulted in Chinatowns being forced into blanket quarantines and Chinese food immediately being rejected by Americans who claimed it to contain rat meat. These incidents show exploitation of the Chinese, in this case, white businessmen scapegoating Chinese people for the plague, which was built upon previous exploitation of the Chinese: property owners not managing their tenements properly, not throwing away trash and neglecting repairs.

Ultimately, however, Chinatown has withstood these historical efforts and its continued survival gives us optimism to project that it can persist despite the coronavirus pandemic. This ability to survive the harm it has historically incurred can be attributed to its unique identity as an immigrant bubble. Chinatowns mainly serve the Chinese communities within themselves and are thus fairly self sufficient bubbles, even in the face of xenophobia. Moreover, such an enclosed immigrant enclave naturally lends itself to forming a strong community with strong community leaders. Chinatown never actually was forced into wholesale demolition as Chinese community leaders continued to defend their civil rights, and while it is true that fear of Chinese spaces spreading disease led to blanket quarantine laws and the burnings of Honolulu's Chinatown to sanitize it, our current federal government does not have the authority to order state quarantines. These are moreso state powers. Honolulu’s Chinatown has since been rebuilt and Chinatown’s presence in American metropolitans is still very strong, because as long as there are large pockets of Chinese Americans, the demand for authentic Chinese cuisine will remain. Even now, the Chinatown community is still venturing out to shop for groceries at local Chinese supermarkets and we are beginning to see the reopening of several Chinatown restaurants, albeit temporarily.

The Emergence of Americanized Chinese Food

But what happens to Chinese restaurants not within the safety of Chinatown?

A large portion of Chinese food’s narrative in America is its adoption into the diets of other American minority groups, and it is at this stage that we begin to see Chinese food shift to the mainstream Chinese American takeout of today. Even while Chinatowns were forced into blanket quarantines, Chinese laundromats spread, a pervasive new business that became a necessity for many non-Chinese minority neighborhoods. Following the laundromats were Chinese takeout restaurants which adapted to serve many Black and Jewish populations and their need for cheap and convenient food. These restaurants began incorporating elements that suited western palates more, such as adding heavy sauces to pack flavor and familiar American vegetables such as carrots and broccoli. These minority groups, although also suffering from social discrimination, still had some impact on what became cool or mainstream. Through entering these palettes, Chinese food gradually also gained white acceptance. Rather than being appreciated for its rich cultural history or unique cooking techniques, Chinese food instead was able to work around xenophobia by adapting to solve food service demands of Westerners.

This food service demand for cheap and tasty food has not gone away with the introduction of the coronavirus. However, when weighed against potential fears of contracting disease, it will probably not be enough to, at least in the short term, ensure the survival of such Chinese restaurants whose clientele are mostly non-Chinese. After all, this acceptance of Chinese takeout cuisine into mainstream culture was very gradual and reluctant. Moreover, these Chinese restaurants will be more so penalized for not being able to adapt to serve popular delivery platforms. Immigrant businesses are notoriously slow in adapting new technology, but in the age of social distancing, this is where the bulk of customers are now ordering from.

A New Wave of Chinese Immigration

Around the same time, the Open Door Policy was passed (1978), leading to the normalization of U.S.-China relations for the first time in decades and causing a second wave of Chinese immigrants to the United States.

With the arrival of airplanes, Chinese immigrants no longer congregated in big cities, but instead began to settle down in larger waves to suburban areas, bringing with them Chinese restaurants beyond the borders of Chinatowns. These restaurants tend to serve Americanized Chinese food in the form of takeout and buffets.

For these Chinese Americans, there is no safety in numbers. In most of these suburban areas, Asian Americans make a very tiny percentage of the population. Limited exposure to Asian faces and culture understandably bolsters the perception of Asian Americans as unfamiliar and foreign.

The increase of Asian American restaurants in majority non-Asian suburbs makes COVID-19’s effects extremely pervasive as these restaurants now encompass a significant portion of the Chinese restaurant industry.

Section III: Conclusion

The world is scared and on the defensive— and not surprisingly so. In such dire circumstances, people will turn towards the familiar to get answers.

In light of this, anti-Chinese sentiment flourishes and takes its toll unequally on Chinese restaurants. Chinatowns have historically proven themselves to be sturdy against external threats because of its internally facing nature. Chinese restaurants outside of Chinatown’s safe boundaries, on the other hand, can expect to face profit delineations due to increasing reservations of its non-Chinese customers about the food’s cleanliness, and we will have to play our part to help prop these essential businesses up.

Our implicit biases born from the historical associations between Chinese immigrants, disease, and unsanitary processes simply will not disappear overnight. The rise of populism, quick readoption of anti-Asian sentiment by our politicians, and increase in hate crimes conveys how deeply ingrained xenophobia is in our culture. Moreover, these biases are being affirmed and perpetuated by the current media portrayal of COVID-19, which continues to alienate the Asian American population through the frequent associations of the disease with the imagery of Asian Americans in masks. As states begin to reopen their businesses and attempt to return to normalcy, we must open our eyes to the xenophobia that has endangered the lives and livelihoods of millions of Asian Americians around the world.

Our address of the rise in xenophobia is not an accusatory stance. Oftentimes, simple cognizance of where we stand in this moment of history, coupled with a willingness to have tough conversations about potential microaggressions, can make important first strides towards eliminating implicit biases.

Namely, it is critical that we work to change media portrayal and public perception of Asians in America. While we cannot stop politicians from using derogatory terms such as the “Chinese Virus” and “Kung Flu,” we can be cautious of our perception of them to make sure such terms do not lead to rash decisions against Chinese businesses altogether. Furthermore, to redirect these biases more head on, our influencers to, whether those be bloggers, celebrities, representatives from new outlets, and especially political figures, make well-known trips to Chinese restaurants and assure people of the cleanliness of these businesses. The public has historically been very receptive to these publicised trips, especially when they are from a

Now, more than ever, we must acknowledge the ever-prevalent implicit biases that shape both our perceptions and actions, and unite in solidarity amid the global pandemic. We should be cautious of repeating history by scapegoating those who have been subject to decades of unjust xenophobia. Only when we move away from this anti-Asian narrative and towards the fact that COVID-19 is a global issue will Chinese-American-run businesses begin to thrive once more.

Bibliography

Abbott, Carl. “The 'Chinese Flu' Is Part of a Long History of Racializing Disease.” CityLab, March 17, 2020. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2020/03/coronavirus-racism-disease-chinatown-bubonic-plague-honolulu/608149/.

Aguilera, Jasmine. “Harmful Xenophobia Spreads Along with Coronavirus.” Time. Time, February 3, 2020. https://time.com/5775716/xenophobia-racism-stereotypes-coronavirus/.

Chang, Julie. “San Francisco Chinatown Affected By Coronavirus Fears, Despite No Confirmed Cases.” NPR. NPR, February 26, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/02/26/809741251/san-francisco-chinatown-affected-by-coronavirus-fears-despite-no-confirmed-cases.

Chen, Yong. “The Rise of Chinese Food in the United States.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.273.

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Employment Situation Summary.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 8, 2020. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm.

Eichelberger, Laura P. “The Politics of an Epidemic: SARS and Chinatown.” Thesis, University of Arizona, 2005.

History.com Editors. “Black Death.” History.com. A&E Television Networks, September 17, 2010. http://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/black-death.

Hooper, Kate, and Jeanne Batalova. “Chinese Immigrants in the United States.” migrationpolicy.org, September 29, 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/chinese-immigrants-united-states-4.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. “Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World.” Essay. In Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World, 443–54. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Jeung, Russell. “Incidents of Coronavirus Discrimination.” Stop AAPI Hate, April 3, 2020. w.asianpacificpolicyandplanningcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/Stop_AAPI_Hate_Weekly_Report_4_3_20.pdf.

Jiang, Hannah and Katie Nixdorf. “Shops in New York City's Chinatown Are Suffering Losses of 50% Because of Coronavirus Fears.” Business Insider. Business Insider, March 6, 2020. http://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-chinatown-flushing-queens-new-york-city-2020-3.

Naylor, Brian. “Fact Check: A Blanket National Quarantine Is Likely Not Legal.” NPR. NPR, April 2, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/02/825293201/a-president-is-not-able-to-order-a-national-quarantine-experts-say.

Norton, Henry Kittredge. “The Chinese.” In The Story of California from the Earliest Days to the Present, 283–96. Chicago, IL: A.C. McClurg, 1913.

Jantz, Shirley. “Prices for 1860, 1872, 1878 and 1882 — Groceries, Provisions, Dry Goods & More.” Choosing Voluntary Simplicity. Accessed May 12, 2020. http://www.choosingvoluntarysimplicity.com/prices-for-1860-1872-1878-and-1882-groceries-provisions-dry-goods-more/.

Ramirez, Rachel. “How a Chinese Immigrant Neighborhood Is Struggling amid Coronavirus-Related Xenophobia.” Vox. Vox, March 14, 2020. http://www.vox.com/identities/2020/3/14/21179019/xenophophia-chinese-community-sunset-park.

Risse, Guenter B. Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco's Chinatown. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Rogers, Katie and Lara Jakes and Ana Swanson. “Trump Defends Using 'Chinese Virus' Label, Ignoring Growing Criticism.” The New York Times. The New York Times, March 18, 2020. http://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/us/politics/china-virus.html.

Rude, Emelyn. “Chinese Food in America: A Very Brief History,” February 8, 2016. https://time.com/4211871/chinese-food-history/.

Tappe, Anneken. “30 Million Americans Have Filed Initial Unemployment Claims since Mid-March.” CNN. Cable News Network, April 30, 2020. http://www.cnn.com/2020/04/30/economy/unemployment-benefits-coronavirus/index.html.